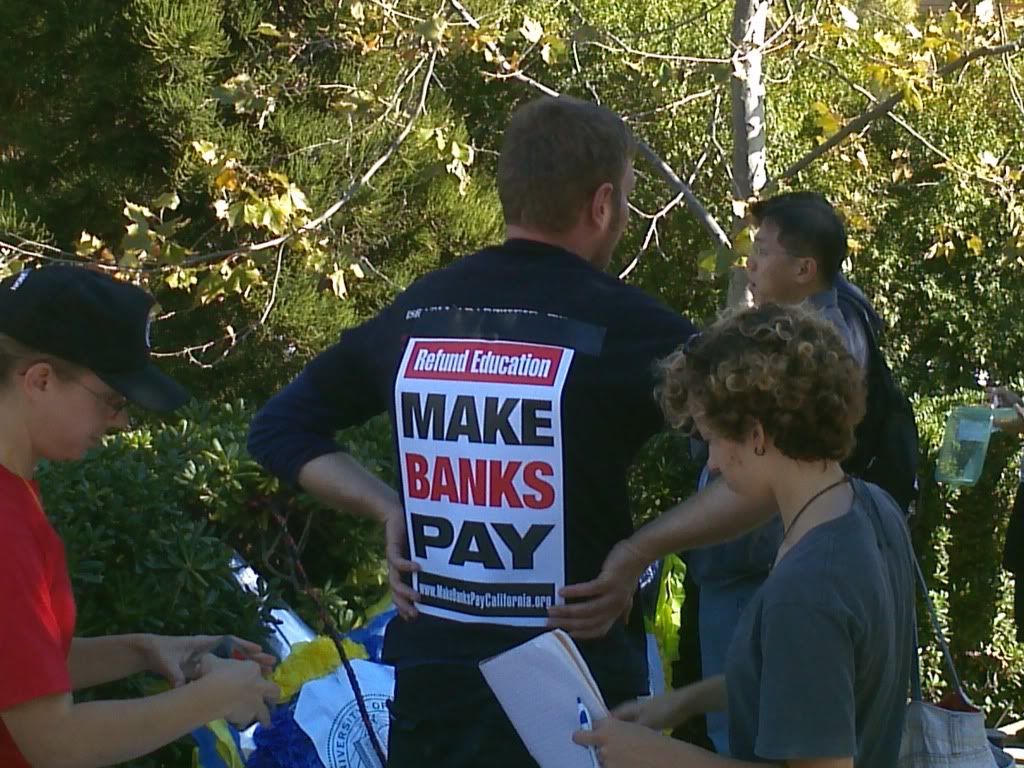

I thought that I would take the time to write a brief end of the year posting. Most likely, I won't have the time or inclination to do this tomorrow, so I might as well put something up tonight. It's been a curious year. At the local level, this year has seen the success of the reform movement in the grad student movement, quickly moving from the challenges to the last contract to a strong, state-wide movement that successfully won all positions on the union's executive board. From there, the local has been at the center of the attempt to revive the movement to defend public education. Schools across the state have been involved in occupations, demonstrations, and disruptions. The most notable actions occurred in Davis and Berkeley, but all the schools with heavy AWDU contingents have managed substantial political actions. The local still needs to make up for the years of neglect in regards to its workplace organizing. I still think that this is going to be a lot of work, particularly without any real models for the kind of work we are involved, but I think that we can still produce a strong rank and file union by the time the contract is up in a couple years.

At the national level, the 'occupy' movement seems to present an opening for counter-systemic movements that doesn't really have an equivalent in my life time. The movement has its obvious origins in the Arab Spring, but that impetus quickly translated into a method to fuse a number of disparate struggles. The closest comparison might be the anti-globalization movement, but it never produced a linkage between the local, the national, and the international that we see here. Additionally, the protests are remarkably popular. Repeatedly in polls, over half the population supports the basic aims of the movement, giving the movement a popularity that the ant-war movement certainly didn't see. The shift from the encampment structure to the attempt to protect houses from foreclosure seems to be a potentially powerful shift for the winter months. I can see two potential points of collapse. 1. A collapse of the delicate structure of alliances, between radicals and liberals, anarchists and socialists, veteran activists and new recruits, as well as a diversity of racial and ethnic groups. 2. The presidential election is going translate into some pretty substantial attempts on the part of the democratic party to translate the movement into a prop for the Obama election. I don't know whether these potential crises will be negotiated or not, but they represent the potential of the movement, in the form of previously unimaginable political assemblages and through a movement that is large enough to potentially change the fate of presidential elections.

The productive problems of both levels of struggle gesture towards the need to reconsider the second type of knowledge as discussed in Spinoza's Ethics, common notions. We need new forms of organization, new forms of communication, and new ways of communicating. I don't know what those new forms are, or if we are capable of producing the kind of novum implicit in these new commons. I think that we need to try to hold onto a little more theoretical modesty in regards to these questions. If these new forms are created, they will be created collectively and in struggle. In this context, we must take up Hegel's demand that we 'tarry with the negative' in order to produce new concepts, that is, the need to refuse the desire to synthesize antagonisms, to flatten ambiguities, and to accept the existence of the unknown. Experimentation and failure are crucial to social movements, no matter how painful they are at times. I'm looking forwards to finding out what happens in the next year, along with finishing a dissertation.

Work Resumed on the Tower is a blog focused on popular culture, literature, and politics from a radical, anti-capitalist perspective.

Saturday, December 31, 2011

Wednesday, December 28, 2011

A short reading of the beginning of Chapter 2 in Karl Marx's Capital Vol. 1

Before I got sick, I began another attempt of reading Marx's Capital, Vol. 1. Up until now, I have only worked through about half the text, getting distracted by other projects, some significant, some less than significant. Remarkably enough, I found reading the text on the airport quite productive. I managed to work through the first two chapters of the text, while on the plane. A lot of it was review, but a number of passages stood out upon increased scrutiny. Marx's literary interests become increasingly apparent in the section on the commodity fetish, and continue into the chapter on exchange. However, the opening passage of that second chapter, "The Process of Exchange" stood out in particular, given my current dissertation project. Marx opens that chapter by describing the relationship between the commodity forms and their 'guardians.'

"Commodities cannot themselves got to market and perform exchanges in their own right. We must, therefore, have recourse to their guardians, who are the possessors of commodities. Commodities are things, and therefore lack the power to resist man. If they are unwilling, he can use force; in other words, he can take possession of them. In order that these objects may enter into relation with each other as commodities, their guardians must place themselves in relation to one another as persons who will reside in those objects, and must behave in such a way that each does not appropriate the commodity of the other, and alienate his own, except through an act to which both parties consent. The guardians must therefore recognize each other as owners of private property. This juridical relation, whose form is the contract, whether as part of a developed legal system or not, is a relation between two wills which mirrors the economic relation. The content fof this juridical relation (or relation of two wills) is itself determined by the economic relation. Here the persons exist for one another merely as representatives and hence owners, of commodities. As we proceed to develop our investigation, we shall find, in general, that the characters who appear on the economic stage are merely personifications of economic relations; it as the bearers (Traeger) of these economic relations that they come to contact with each other.

What chiefly distinguishes a commodity from its owner is the fact that every other commodity counts for it only as the form of appearance of its own value. A born leveller and cynic, it is always ready to exchange not only soul, but body with each and every other commodity, be it more repulsive than Maritornes herself. The owner makes up for this lack in the commodity of a sense of the concrete, physical body of the other commodity, by his own five and more senses. For the owner, his commodity possesses no direct use-value. Otherwise, he would not bring it to market. It has use-value for others; but for himself its only direct use-value is as a bearer of exchange-value, and consequently, a means of exchange. He therefore makes up his mind to sell it in return for commodities whose use-value is of service to him. All commodities are non-use-values for their owners, and use-values for their non-owners. Consequently, they must all change hands. But this changing of hands constitutes their exchange, and their exchange puts them in relation with each other as values and realizes them as values. Hence commodities must be realized as values before they can be realized as use-values." (Marx 179)

Marx's description of this relationship takes on a particularly patriarchal valence. The figure of the guardian is necessary for the commodity form, but the relationship is defined in terms of potential coercion. Marx notes, "Commodities are things, and therefore lack the power to resist man." The commodity is labelled a thing, but it is strangely animated by the relationship with its guardian. 'He' (to use Marx's language) can 'use force' or 'take possession' of the commodity in order to bring it into the market. The commodity may be a thing, but it is haunted by a phantom-like volition that must be potentially dominated in order to bring into the set of relations that define the market. To return to the question of patriarchy, its difficult to avoid the implications of rape contained in the word, 'force.' If this seems like an overreach, the following paragraph describes the relationship in sexual terms, or perhaps more specifically, as a form of prostitution. The 'guardian' puts the commodity form into an endless series of both intimate and degrading exchanges, oscillating between the antagonistic poles of use and exchange. The violent intimacy of the commodity is opposed by the guarded relationship of the guardians themselves. Haunted by the threat of dispossession, that is, of facing the kind of violation contained in the exchange of commodities, the guardians set up a thick set of laws to avoid that potential threat.

However, the 'guardian' of the commodity doesn't escape this relationship unscathed. As Marx notes, "the persons exist for one another merely as representatives and hence owners, of commodities." Hemmed in by the logic of private property, the commodity 'guardian' or owner is flattened or objectified, just as the commodity is personified in exploitation and domination. The patriarchal logic of instrumental reason reflects back on those who wield it, transforming them into mere representatives, equally trapped by the structure of domination that they created. Marx makes this explicit with the following passage, "As we proceed to develop our investigation, we shall find, in general, that the characters who appear on the economic stage are merely personifications of economic relations; it as the bearers (Traeger) of these economic relations that they come to contact with each other." Marx's term to describe this term is Traeger, translated as bearer by Ben Fowkers, the term also implies that the object plays the role as receptacle or repository. In effect, the 'guardian' is himself an empty signifier, as infinitely exchangeable as the commodity itself. The 'guardian' becomes a curious type of cypher, one that uses 'his own five and more senses' to represent the 'economic relation', which 'mirrors' or 'determines' the social relations between 'guardians.' Marx describes this form of representation as 'ownership.' If the commodity form is personified by the social relations in its production, its 'guardian' is transformed into an object.

It's fairly obvious that the domination and expropriation of living labor is thinly veiled by the mystified form of the commodity, which explains the threat of force contained in the relationship between guardian and commodity. However, the patriarchal metaphor shouldn't be ignored. We can already see a glimpse of the critique written by Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer in Dialectic of Enlightenment, and, perhaps more significantly, a possible feminist engagement with Marx, avoiding a reading that simply operates in the logic of lack. We can see in Marx's work, a sort of libidinal economy contained in the commodity form itself, one that arises out of the domination of production and colonizes the entire social field. The role of patriarchy in the so called primitive accumulation of capital described historically by Sylvia Federici in Caliban and the Witch is already implied by Marx in the logical form of his analysis. Marx continually insists that the commodity form contains in it the social relations of its production, and therefore the dispossession necessary for its genesis. All to often, Marxists gesture towards this network of social relations without working through the full meaning of that implication. Perhaps it is time to take that up.

"Commodities cannot themselves got to market and perform exchanges in their own right. We must, therefore, have recourse to their guardians, who are the possessors of commodities. Commodities are things, and therefore lack the power to resist man. If they are unwilling, he can use force; in other words, he can take possession of them. In order that these objects may enter into relation with each other as commodities, their guardians must place themselves in relation to one another as persons who will reside in those objects, and must behave in such a way that each does not appropriate the commodity of the other, and alienate his own, except through an act to which both parties consent. The guardians must therefore recognize each other as owners of private property. This juridical relation, whose form is the contract, whether as part of a developed legal system or not, is a relation between two wills which mirrors the economic relation. The content fof this juridical relation (or relation of two wills) is itself determined by the economic relation. Here the persons exist for one another merely as representatives and hence owners, of commodities. As we proceed to develop our investigation, we shall find, in general, that the characters who appear on the economic stage are merely personifications of economic relations; it as the bearers (Traeger) of these economic relations that they come to contact with each other.

What chiefly distinguishes a commodity from its owner is the fact that every other commodity counts for it only as the form of appearance of its own value. A born leveller and cynic, it is always ready to exchange not only soul, but body with each and every other commodity, be it more repulsive than Maritornes herself. The owner makes up for this lack in the commodity of a sense of the concrete, physical body of the other commodity, by his own five and more senses. For the owner, his commodity possesses no direct use-value. Otherwise, he would not bring it to market. It has use-value for others; but for himself its only direct use-value is as a bearer of exchange-value, and consequently, a means of exchange. He therefore makes up his mind to sell it in return for commodities whose use-value is of service to him. All commodities are non-use-values for their owners, and use-values for their non-owners. Consequently, they must all change hands. But this changing of hands constitutes their exchange, and their exchange puts them in relation with each other as values and realizes them as values. Hence commodities must be realized as values before they can be realized as use-values." (Marx 179)

Marx's description of this relationship takes on a particularly patriarchal valence. The figure of the guardian is necessary for the commodity form, but the relationship is defined in terms of potential coercion. Marx notes, "Commodities are things, and therefore lack the power to resist man." The commodity is labelled a thing, but it is strangely animated by the relationship with its guardian. 'He' (to use Marx's language) can 'use force' or 'take possession' of the commodity in order to bring it into the market. The commodity may be a thing, but it is haunted by a phantom-like volition that must be potentially dominated in order to bring into the set of relations that define the market. To return to the question of patriarchy, its difficult to avoid the implications of rape contained in the word, 'force.' If this seems like an overreach, the following paragraph describes the relationship in sexual terms, or perhaps more specifically, as a form of prostitution. The 'guardian' puts the commodity form into an endless series of both intimate and degrading exchanges, oscillating between the antagonistic poles of use and exchange. The violent intimacy of the commodity is opposed by the guarded relationship of the guardians themselves. Haunted by the threat of dispossession, that is, of facing the kind of violation contained in the exchange of commodities, the guardians set up a thick set of laws to avoid that potential threat.

However, the 'guardian' of the commodity doesn't escape this relationship unscathed. As Marx notes, "the persons exist for one another merely as representatives and hence owners, of commodities." Hemmed in by the logic of private property, the commodity 'guardian' or owner is flattened or objectified, just as the commodity is personified in exploitation and domination. The patriarchal logic of instrumental reason reflects back on those who wield it, transforming them into mere representatives, equally trapped by the structure of domination that they created. Marx makes this explicit with the following passage, "As we proceed to develop our investigation, we shall find, in general, that the characters who appear on the economic stage are merely personifications of economic relations; it as the bearers (Traeger) of these economic relations that they come to contact with each other." Marx's term to describe this term is Traeger, translated as bearer by Ben Fowkers, the term also implies that the object plays the role as receptacle or repository. In effect, the 'guardian' is himself an empty signifier, as infinitely exchangeable as the commodity itself. The 'guardian' becomes a curious type of cypher, one that uses 'his own five and more senses' to represent the 'economic relation', which 'mirrors' or 'determines' the social relations between 'guardians.' Marx describes this form of representation as 'ownership.' If the commodity form is personified by the social relations in its production, its 'guardian' is transformed into an object.

It's fairly obvious that the domination and expropriation of living labor is thinly veiled by the mystified form of the commodity, which explains the threat of force contained in the relationship between guardian and commodity. However, the patriarchal metaphor shouldn't be ignored. We can already see a glimpse of the critique written by Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer in Dialectic of Enlightenment, and, perhaps more significantly, a possible feminist engagement with Marx, avoiding a reading that simply operates in the logic of lack. We can see in Marx's work, a sort of libidinal economy contained in the commodity form itself, one that arises out of the domination of production and colonizes the entire social field. The role of patriarchy in the so called primitive accumulation of capital described historically by Sylvia Federici in Caliban and the Witch is already implied by Marx in the logical form of his analysis. Marx continually insists that the commodity form contains in it the social relations of its production, and therefore the dispossession necessary for its genesis. All to often, Marxists gesture towards this network of social relations without working through the full meaning of that implication. Perhaps it is time to take that up.

Tuesday, December 27, 2011

Notes on the Post-War Period

Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique opens with her identification of a gap or lacunae in the dense network of discourse surrounding the household, a gap identified with the yearning of women.

“For over fifteen years there was no word of this yearning in the millions of words written about women, for women, in all the columns, books and articles by experts telling women their role was to seek fulfillment as wives and mothers. Over and over women heard in voices of tradition and of Freudian sophistication that they could desire no greater destiny than to glory in their own femininity. Experts told them how to catch a man and keep him, how to breastfeed children and handle their toilet training, how to cope with sibling rivalry and adolescent rebellion; how to buy a dishwasher, bake bread, cook gourmet snails, and build a swimming pool with their own hands; how to dress, look, and act more feminine and make marriage more exciting; how to keep their husbands from dying young and their sons from growing into delinquents. They were taught to pity the neurotic, unfeminine women who wanted to be poets or physicists or presidents…. A thousand expert voices applauded their femininity, their adjustment, their new maturity. All they had to do was devote their lives from earliest girlhood to finding a husband and bearing children.” (Friedan 58)

The unnamed problem discussed by Friedan is defined by its dialectical opposite, the utopian promise of an expertise created through a dense discourse of scientific and technical expertise, in the form of technical manuals, psychoanalysis, and social convention. Friedan gestures towards an intense instrumentalization of the household through the construction of a dense web of discourse. The care of the bourgeois family is mapped out in painstaking detail, through the minutiae of childcare, the management of resources, and most of all, the affective economy of femininity. Friedan recognizes the intense social, political, and economic pressure being put on the newly reconstructed household, intuitively recognizing the radical shift in the economy of the family in the post war years described by Stephanie Coontz. The figure of the mother can be found at the center of that nexus, linking shifts in political, social and libidinal economies. Rather than following Friedan’s repressive hypothesis, I want to read the ‘feminine mystique’ as the symptom of the intensification of the body of the white mother, transforming her into the guarantor of the stability of not only the household, but the nation itself, linking to the creation of what Stuart Ewen calls consumer social democracy as well as introducing the working classes to the regime of sexuality. These hegemonic structures along with the expansion and reintegration of the white supremacist order were intended to legitimate and reinforce the logic of capitalist accumulation.

Within that economy, ‘expertise’ and ‘yearning’ are mutually constitutive, operating within a sort of dialectical relationship. In her recognition of the dialectical relationship between ‘expertise’ and ‘yearning, Friedan implicitly develops a sort of class analysis, recognizing a common set of experiences between (white) women centered in the psychic, social, political, and economic structures of the household, which crossed ostensible class barriers. The labor of the household becomes a central locus of complex set of techniques of population, legitimizing the Fordist regime of accumulation, and perhaps more significantly, operating as a locus meant to stabilize the social reproduction of the newly expand regime of accumulation. In effect, the structures of affective labor and forms of consumption are central to mitigating the alienation of the workplace, continuing a regime of consumption, but perhaps more significantly, reproducing the population. The mother becomes the focus for this web of discourse not because of irrelevance as Friedan occasionally thinks, but because these modes of unpaid labor are central to the regime as a whole. That centrality, in turn, produces the modes of resistance gestured towards in Friedan's choice of language, 'yearning.' Feminism becomes the primary, but not exclusive form of resistance to this regime.

In their work, Empire, Antonio Negri and Michael Hardt argue that the current regime of accumulation is increasingly defined by modes of affective labor. I'm interested in exploring the role that feminism as a form of counter-conduct to Fordist capital and the various attempts to appropriate those forms of counter-conduct coagulate into the current regime of accumulation.

Sunday, December 25, 2011

Activism, Science Fiction Studies, and Cultural Studies Covered Briefly in Three Paragraphs

I'm currently in Minneapolis, trying to get over a mild, but nagging cold. It's about one in the morning before Christmas. Why not start a blog posting? I'm going to try to get back into the swing of writing with a great deal more regularity than I have over the past few months. More specifically, I plan to return to some of the more academic topics that have gotten dropped a bit lately for more immediately focused projects and polemics. It's not that I plan to drop that material, but I want to get back to some of the earlier discussions around cultural studies, science fiction, and critical theory that have found less emphasis in the blog lately. Part of that has occurred because I have been recently been dealing with the potential loss of two chapters worth of my dissertation, but another part has simply occurred because my thoughts have been focused on a number of immediate political concerns, particularly about the question about organizing the Irvine branch of the local union, and the attempt to create a coalition in defense of public education on campus. I'm certainly not going to drop this stuff. I'm still trying to get the local and myself to think about doing the day to day work of organizing, of moving away from the informal friendship structure of the current situation to something that is a genuine rank and file structure. Additionally, I have some very definite ideas about some experiments that might make good actions for the coalition, and am trying to get Sylvia Federici and George Caffentzis to give a couple talks at the university about the question of debt as well as the history of social movements.

But I also want to turn to some of the questions that brought me to the institution itself, questions that are themselves, but are a bit more untimely, to use Nietzsche's phrase. My research for my dissertation has turned increasingly to the intertwined topics of the utopian form and structures of domestic conventionality. These generic forms find their first major interconnection with the work of Charlotte Perkins Gilman. Critics often write about Gilman's utopian novel, Herland, but ignore the context of its publication, Gilman's self-published magazine, The Forerunner. The majority of Gilman's novels were published in that magazine, including her major utopian works, Moving the Mountain, Herland, and With Her in Ourland. These novels were serialized along with popular sociological material, and perhaps more significantly, types of writing that could fit very comfortably within a conventional women's magazine, despite its political content. In many ways, The Forerunner isn't as exceptional a publication as many seem to think that it was. Progressive era publications, including women's magazines, often took on serious political topics, and editors of the journals included naturalist author Theodore Dreiser. What is perhaps unique to the work of the The Forerunner is the attempt to synthesize the utopianism that Gilman derives from the work of Edward Bellamy and link it with the conventions of domestic melodrama. If Herland frequently operates under the logic of the feminine mystique, the conventional dramas about marriage and domestic life show a curious fascination with long economic exposition, frequently consisting of lists of costs. In effect, Gilman attempts to negotiate her focus on household domesticity through generic form.

Additionally, the question of cultural studies remains a continued interest, particularly around questions of subculture, everyday life, and the limits of capital contained in the contradictions contained in the commodity form. The material that I am working with is obviously intensely commodified, and the rise of the genre of science fiction is linked to the rise of Fordist regime of accumulation, or perhaps more crudely, a society built on mass consumption. The rise of paraliterature strongly parallels these economic shifts. This is frequently gestured towards in the Marxist work on science fiction, following Darko Suvin, but it is rarely worked through. Similarly feminist work does some impressive work of developing an analysis of the subcultural networks that form the critical apparatus of the genre, but don't take on the Lukacsian questions of form and history. To be honest, I'm not sure if I can do this work within my dissertation, which is focused on trying to produce a type of social formalism, but I think I'm going to try to use the blog to try to ask these questions. One of the things that I was really fascinated by in the early editorials of science fiction writer and editor Judith Merril was the way that she linked questions of literary quality with the commodity form, ie, the quality of the literature somehow paralleled the production of quality paperbacks, of the existence of hard cover science fiction novels, etc. There are similar thoughts in some of the criticism of Damon Knight, and even to an extent in the early work of Samuel Delaney. I think I am going to think through some of those histories more extensively. In any case, I think that I am going to keep this transitional Christmas post brief, and leave it there.

But I also want to turn to some of the questions that brought me to the institution itself, questions that are themselves, but are a bit more untimely, to use Nietzsche's phrase. My research for my dissertation has turned increasingly to the intertwined topics of the utopian form and structures of domestic conventionality. These generic forms find their first major interconnection with the work of Charlotte Perkins Gilman. Critics often write about Gilman's utopian novel, Herland, but ignore the context of its publication, Gilman's self-published magazine, The Forerunner. The majority of Gilman's novels were published in that magazine, including her major utopian works, Moving the Mountain, Herland, and With Her in Ourland. These novels were serialized along with popular sociological material, and perhaps more significantly, types of writing that could fit very comfortably within a conventional women's magazine, despite its political content. In many ways, The Forerunner isn't as exceptional a publication as many seem to think that it was. Progressive era publications, including women's magazines, often took on serious political topics, and editors of the journals included naturalist author Theodore Dreiser. What is perhaps unique to the work of the The Forerunner is the attempt to synthesize the utopianism that Gilman derives from the work of Edward Bellamy and link it with the conventions of domestic melodrama. If Herland frequently operates under the logic of the feminine mystique, the conventional dramas about marriage and domestic life show a curious fascination with long economic exposition, frequently consisting of lists of costs. In effect, Gilman attempts to negotiate her focus on household domesticity through generic form.

Additionally, the question of cultural studies remains a continued interest, particularly around questions of subculture, everyday life, and the limits of capital contained in the contradictions contained in the commodity form. The material that I am working with is obviously intensely commodified, and the rise of the genre of science fiction is linked to the rise of Fordist regime of accumulation, or perhaps more crudely, a society built on mass consumption. The rise of paraliterature strongly parallels these economic shifts. This is frequently gestured towards in the Marxist work on science fiction, following Darko Suvin, but it is rarely worked through. Similarly feminist work does some impressive work of developing an analysis of the subcultural networks that form the critical apparatus of the genre, but don't take on the Lukacsian questions of form and history. To be honest, I'm not sure if I can do this work within my dissertation, which is focused on trying to produce a type of social formalism, but I think I'm going to try to use the blog to try to ask these questions. One of the things that I was really fascinated by in the early editorials of science fiction writer and editor Judith Merril was the way that she linked questions of literary quality with the commodity form, ie, the quality of the literature somehow paralleled the production of quality paperbacks, of the existence of hard cover science fiction novels, etc. There are similar thoughts in some of the criticism of Damon Knight, and even to an extent in the early work of Samuel Delaney. I think I am going to think through some of those histories more extensively. In any case, I think that I am going to keep this transitional Christmas post brief, and leave it there.

Thursday, December 22, 2011

tentative notes on the state of the union

I haven't written as much as I would have liked to do in the past couple of months. I've been distracted by my work for the union, and the effort to produce a movement to defend public education at both the local level, as well as the state level. Within that context, I thought it might be worth briefly discussing what's been going on within the Irvine branch of the local. Most of my postings about the local have been polemical in nature, focusing on the conflicts with the former leadership or conflicts with the former leadership, but this posting is going to be a little more open ended. To put it simply, our reform group, AWDU has been in charge of the local for the past quarter. At this point, it might be worth asking what we have accomplished at this point. I'm not going to get into the larger debates about the state, although some of the concerns around the Irvine campus may tie into larger concerns around the campus.

To start off with some of the positive aspects of the past few months, the Irvine branch has managed to produce a fairly large activist base. We currently have a listserve with about thirty activists on it, and, for the first time in years, we actually have all of our Joint Council positions filled. Additionally, we have a number of steward positions filled by activists. This has translated into monthly membership meetings with large numbers, the attempt to organize a number of committees to focus on campus issues, and a number of cultural events. The former leadership at our campus always insisted that the Irvine campus was intrinsically conservative, and the rank and file preferred to let a small group of people make the decisions for the union, but I think the recent shifts point to the fact that this may have been a self-fulfilling prophecy. We still have a lot of work on this front, particularly within the natural sciences, but the shift in the local has been considerable.

The local branch of the union has also been involved in the attempt to recreate the coalition to defend public education that more or less fell apart after the large demonstrations in March. In this regard, there has been some meaningful success. Despite the fact that the Irvine campus hasn't seen the drama and militancy that has been seen on the Davis, Irvine, and Santa Cruz campuses, the campus has managed to produce a significant coalition space, and has also managed to organize protests, and contribute to the protest against the California State University trustees in Long Beach, as well the UCLA regents meeting. The direction of this coalition and its sustainability is still very much in the air. A number of the issues that destroyed the 2009-2010 coalition, particularly around the issue of race and perhaps more specifically, the colonial legacy of the term 'occupation' and the attempt by one participant to argue for a focus on economics, rather than race, revealed themselves in the last general meeting. (a lot more needs to be said here, particularly around the need for us to meaningfully commit to anti-racist politics, but I feel neither the ability to take this on now.) Within that context, the concept of 'occupation' is still viewed with a deep suspicion on the part of many of the undergraduate organizers, particularly the activists of color. Furthermore, the movement has not linked itself to the broad student body despite a successful demonstration of about 300-500 people. We managed to accomplish quite a bit in the past months, but we're going to need to launch a massive educational event, and perhaps more significantly, create forms of militancy that don't mirror the protests of the northern campuses. (We also need to learn how to run better meetings, and call people on their nonsense, as well.)

As a brief side note, the guilty verdict for the Irvine 11 has played a considerable chilling effect on much of the campus. That verdict led to the choice on the part of the Irvine 19 to take plea deals, as well as making prosecution a much more real threat for on campus activism.

Moving away from the question of coalition activism to day to day rank and file activism, we can see another substantial problem. As I previously noted, the local unit has done a very good job of recruiting a powerful activist base, one that exists primarily in the social sciences and the humanities, but having representation throughout the disciplines. The next step, making the union a presence in the workplace of the rank and file, has not yet occurred. The AWDU group was able to successfully out organize the lone USEJ representative through a combination of resentments around the last contract, and more significantly, the variety of informal social networks. That set of networks continued to produce an activist base for the campus, but efforts to move beyond this situation have been less successful, particularly in bringing in new membership, and more significantly, translating the right to collective bargaining into on the ground worker's power. I don't want to say that this problem hasn't been implicitly recognized by the group, but the effort to create subcommittees hasn't translated into practical action, and the proposed organizing committee and departmental meetings have yet to occur. We were right to reject the representational structure that the former leadership operated under, a structure that operated on an instrumental logic, but we haven't as of yet come up with alternative structures. This seems to be the central question, along with the need to produce a new student movement in Irvine.

To start off with some of the positive aspects of the past few months, the Irvine branch has managed to produce a fairly large activist base. We currently have a listserve with about thirty activists on it, and, for the first time in years, we actually have all of our Joint Council positions filled. Additionally, we have a number of steward positions filled by activists. This has translated into monthly membership meetings with large numbers, the attempt to organize a number of committees to focus on campus issues, and a number of cultural events. The former leadership at our campus always insisted that the Irvine campus was intrinsically conservative, and the rank and file preferred to let a small group of people make the decisions for the union, but I think the recent shifts point to the fact that this may have been a self-fulfilling prophecy. We still have a lot of work on this front, particularly within the natural sciences, but the shift in the local has been considerable.

The local branch of the union has also been involved in the attempt to recreate the coalition to defend public education that more or less fell apart after the large demonstrations in March. In this regard, there has been some meaningful success. Despite the fact that the Irvine campus hasn't seen the drama and militancy that has been seen on the Davis, Irvine, and Santa Cruz campuses, the campus has managed to produce a significant coalition space, and has also managed to organize protests, and contribute to the protest against the California State University trustees in Long Beach, as well the UCLA regents meeting. The direction of this coalition and its sustainability is still very much in the air. A number of the issues that destroyed the 2009-2010 coalition, particularly around the issue of race and perhaps more specifically, the colonial legacy of the term 'occupation' and the attempt by one participant to argue for a focus on economics, rather than race, revealed themselves in the last general meeting. (a lot more needs to be said here, particularly around the need for us to meaningfully commit to anti-racist politics, but I feel neither the ability to take this on now.) Within that context, the concept of 'occupation' is still viewed with a deep suspicion on the part of many of the undergraduate organizers, particularly the activists of color. Furthermore, the movement has not linked itself to the broad student body despite a successful demonstration of about 300-500 people. We managed to accomplish quite a bit in the past months, but we're going to need to launch a massive educational event, and perhaps more significantly, create forms of militancy that don't mirror the protests of the northern campuses. (We also need to learn how to run better meetings, and call people on their nonsense, as well.)

As a brief side note, the guilty verdict for the Irvine 11 has played a considerable chilling effect on much of the campus. That verdict led to the choice on the part of the Irvine 19 to take plea deals, as well as making prosecution a much more real threat for on campus activism.

Moving away from the question of coalition activism to day to day rank and file activism, we can see another substantial problem. As I previously noted, the local unit has done a very good job of recruiting a powerful activist base, one that exists primarily in the social sciences and the humanities, but having representation throughout the disciplines. The next step, making the union a presence in the workplace of the rank and file, has not yet occurred. The AWDU group was able to successfully out organize the lone USEJ representative through a combination of resentments around the last contract, and more significantly, the variety of informal social networks. That set of networks continued to produce an activist base for the campus, but efforts to move beyond this situation have been less successful, particularly in bringing in new membership, and more significantly, translating the right to collective bargaining into on the ground worker's power. I don't want to say that this problem hasn't been implicitly recognized by the group, but the effort to create subcommittees hasn't translated into practical action, and the proposed organizing committee and departmental meetings have yet to occur. We were right to reject the representational structure that the former leadership operated under, a structure that operated on an instrumental logic, but we haven't as of yet come up with alternative structures. This seems to be the central question, along with the need to produce a new student movement in Irvine.

Tuesday, November 29, 2011

Fate, Desire, and the Crisis of Individualism in Pierre

Perhaps we should open up with a simple question, what is one to do with Pierre? Melville produced this novel a year after Moby Dick, ostensibly to produce a novel that was more in the tastes of the genteel reading public, the ‘milk’ in contradistinction to the ‘sea-salt’ of Moby Dick. And yet we are given this monstrosity. I choose the word monstrosity rather carefully, not as to indict the formulations of kinship that occur in the book, but instead to point to the strangely grafted quality of the text. Juxtaposed within the text, we find obvious references to Shakespeare’s tragedies, the poetry of Dante, rather badly read philosophy, Greek myth, etc. The book cuts abruptly to a digression of an assessment of Pierre’s literary career of which we are only just privy to through the digression.

However I plan on touching on three separate topics within the book. The first deals with the way that the family history of Herman Melville circulates within the text. This will then move into a discussion of the notion of ‘fate that is circulated through the book. I look at the connections that this has with Melville’s earlier novel Moby Dick, and look at how this connects to desire. From there I want to move into a discussion of the structures of kinship that work within the book, which are always within a state of transgression. All of these coalesce in the desire for individualism, a desire that is intimately linked to the repression of that which allowed for the subject’s production.

It’s difficult to discuss the book Pierre without noting some of the prominent similarities between the heritage of Pierre and Melville’s own life. I turn briefly to CLR James’ reading for some of these details.

Both his grandfathers were heroes of the Revolutionary War. His father was a merchant, an importer of foreign merchandise. Melville was thus by birth a member of that landed and commercial aristocracy which, even after 1776, held the first place in American society until Andrew Jackson gave it a mortal wound in 1828. The Melville family felt this personally. Herman’s grandfather, Major Thomas Melville, was removed as Naval officer for the Port of Boston by the new Jackson administration. Other calamities were in store. In 1832 a depression ruined his father and the blow caused his death. The Melvilles were ruined. Herman was then thirteen years old. Around him, henceforward, the old America was passing, and a new America was taking its place in a turmoil that grew increasingly.

Machine production was breaking up the old artisan industry. Between 1840 and 1850, far from the frontier offering an outlet for the bold and energetic in the East, there was a movement back from the farms to the cities. The old sense that men had of being members of an integrated community, which the winning of Independence had not destroyed, was now in process of dissolution. This is a society in which young Melville grew up. Unchecked individualism was coming to maturity and Emerson, a favorite author of Henry Ford, understood the change and celebrated it.[1]

We find ourselves confronted with an image that is extraordinarily similar to the familial background of our main character, Pierre. I am, of course, aware of the injunction that we are not to read the biography of the author into the text, but Melville is a rather interesting case in this instance. Despite the failure of Moby Dick, Melville could be argued to be one of the first examples of what could be called a celebrity writer, and what’s more one that succeeds within this project through a certain project of self-mythologisation. The text of this history is not only written into the text of his novels, but also into a countless series of newspaper and magazine articles. I would argue that the figure of the history of Melville is a much of an act of intertextuality as the incorporation of the texts of Dante or Shakespeare.

Similarly Melville sites himself within his text. This can be found in the descriptions in the family life of Pierre, the reception of the critics to his works, and a number of other places. I would like to connect this with the torn pamphlet that Pierre reads in the middle of the novel, “Lecture First. Chronometricals and Horologicals.” “For peculiarly coming from God, the sole source of that heavenly truth, and the great Greenwich hill and tower from which the heavenly truth, and far out into infinity reckoned; such souls seem as London sea-chronometers (Greek, time-namers) which as the London ship floats past Greenwich down the Thames, are accurately adjusted by Greenwich time, will still give that same time, even though carried to the Azores.”[2] The piece goes on with the analogy, arguing that the chronometer would act out of sync with the times of China. One could say that one is only a time-namer for a particular place, and perhaps even time.

I want to read Pierre within this notion that Melville introduces us to, that of the ‘chronometer, the time-namer.’ We have already touched on the notion of transition earlier in our discussion. James the good marxist that he is has already noted for us that there was a radical shift in the nature of the republic that was occurring at that time, this is marked by all the usual signs of industrial capitalism, the collapse of artisan production, communities, urbanization, etc. But more significantly for this narrative, he marked the production of a sort of unfettered individualism within this. Pierre, and indeed the rise of the figure of Melville, fits well into this narrative. There is an interesting reading of this within Wai-chee Dimock’s Empire for Liberty: Melville and the Poetics of Individualism that reads Melville symptomatically of these times. I am sympathetic to this reading, and never want to suggest that the text escapes this, but it seems that alongside this desire for unfettered individualism is a critical examination of it. After all, the text marks this passage, and notes that Pierre cannot understand it, even upon multiple readings. One cannot act as a time-namer of the collective desire for unfettered individualism and simultaneously recognize that fact.

The figure of Melville operates within this poetics of individualism. He had operated within it for some time before the publication of Pierre. His earliest work was published as a memoir, and his most popular works were published under the authority of a man that has been to sea. He was the man who read into Hawthorne’s Mosses the production of a genuinely American form of art, one that orphaned itself from its European roots. At the same time, the desire to fulfill this narrative placed Melville in opposition to the audience that held that same myth in common. We can see a profound contradiction between the “I” of Melville that desires to be the “great artist” as opposed to the “I” that was desired by the publishers and the audience of the day, an “I” that is associated with a sort of authentic self, and its journeys.

We will need to return to this discussion of the circulation of the politics of the individual that circulates in such a vexed and complicated manner within the text, but we first need to deal with the method in which the plot moves forward, namely the question of fate. This term, which appears frequently within the text, is not unique to it. It also acts as an important feature of the narrative structure of Moby Dick. Ultimately, we will see that it both explains and undercuts the individualism discussed above.

What does it mean to enter into the formation of time, of the times I suppose that Pierre is naming? I want to enter into this discussion with the figure of Fate. Fate is one of the most interesting parallels between the text of Pierre and that of Moby Dick, both are driven by a mysterious force that is given the name ‘Fate.’ For Ishmael, fate is linked to the fatal voyage that he embarks upon. For Pierre (who is also marked as Ishmael within the text) fate enters with the entrance of the letter that will pull him from his old way of life. “He equivocated with himself no more; the gloom of the air had now burst into his heart, and extinguished its light; then, first in all his life, Pierre felt the irresistible admonitions and intuitions of Fate.”[3]

This figure of Fate acts to drive him to secretly visit his illegitimate sister, abandon his finance and mother, marry his half sister and leave his home and city. We can see the intensity that comes from his initial connection with Isabel. “Never had human voice so affected Pierre before. Though he saw not the person whom it came, and though the voice was wholly strange to him, yet the sudden shriek seemed to split its way clean through his heart, and leave a yawning gap there.”[4] Indeed Fate is presented as a powerful force, one that pushes through and beyond the individual. “So, though long previous generations, whether of births of thoughts, Fate strikes the present man. Idly he disowns the blow’s effect, because he felt no blow, and indeed, received no blow. But Pierre was not arguing Fixed Fate and Free Will, now; Fixed Fate and Free Will were arguing him, and Fixed Fate got the better of the debate.”[5]

Indeed, I agree with Cesare Casarino’s reading of Fate within Melville’s economy. “Fate is desire. To catch a glimpse of the future one feels fated to fulfill is here understood as the form taken by the desire for that future, as a claim-staking over its as yet “unapproachable and unknown” territories: to foresee and to want are produced here as the Janus-headed process propelling the discourse of fate…. For Ishmael, fate is produced both as the materialization and as the displacement of a desire too great and unconfessable to be made manifest any form other than a policing exteriority, a ponomphean deus ex machina hovering and looming high above the stage on which the drama of whaling is about to unfold.”[6]

The desire that Casarino is invoking doesn’t operate within the romantic economy even though it can be mystified into such a position. Instead this formation of desire is a productive force that cannot be conceived of either as an outside or a completely immanent force. It cannot be conceive within the economy of the outside because it is so linked to the becoming of the subject in question, but neither can it be conceived as immanent because it draws on the forces that produced the subject. As a force it is productive and overdetermined. It pushes the subject into a futurity that he does not even complete understand himself.

Just as Fate acts within the economy of Moby Dick, there is a comparable role played within Pierre. We can find the explosive nature of this very early within the structure of the novel.

Pierre now seemed distinctly to feel two antagonistic agencies within him; one of which was just struggling into his consciousness, and each of which was striving for the mastery; and between whose respective final ascendencies, he thought he could perceive, though but shadowly, that he himself was to be the only umpire. One bade him finish the selfish destruction of the note; for in some dark way the reading of it would irretrievably entangle his fate. The other bade him dismiss all misgivings; not because there was no possible ground for them, but because to dismiss them was the manlier part, never mind what might betide. This the good angel seemed mildly to say—Read, Pierre, though by reading thou may’st entangle thyself, yet may’st thou thereby disentangle others. Read, and feel that best blessedness which, with the sense of all duties discharged, holds happiness indifferent. The bad angel insinuatingly breathed—Read it not, dearest Pierre; but destroy it, and be happy. Then, at the blast of his noble heart, the bad angel shrunk up into nothingness; and the good one defined itself clearer and more clear, and came nigher and more nigh to him, smiling sadly but benignantly; while fort from the infinite distances wonderful harmonies stole into his heart; so that every vein in him pulsed to some heavenly well. (Melville 63)

In receiving the letter, Pierre has the intuition that this will some how radically change his life, and he is given the choice whether to stay in the place where he is, or move elsewhere. Within that, he decides upon opening the letter. It is curious that while the decision is a displaced one with the figures of angels acting as litigants, the joy that is gained from the decision is Pierre’s even if he cannot fully understand it. And what is contained in the letter but the thing that he has most wanted in the world, a sister. When one looks at the response that Pierre has to the letter, it is clear that his acceptance of its truth is a form of desire for that very truth. One can see this in his final acceptance of the letter.

“This letter is not a forgery. Oh! Isabel, thou art my sister; and I will love thee, and protect thee, ay, and own thee through all. Ah! Forgive me, ye heavens, for my ignorant ravings, and accept this my vow.—Here I swear myself Isabel’s. Oh! Thou poor castaway girl, that in loneliness and anguish must have long breathed the same air, which heaven hath placed in my hands; sweet Isabel! Would I not be baser than brass, and harder, and colder than ice, if I could be insensible to such claims as thine? Thou movest before me, in rainbows spun of thy tears! I see thee long weeping, and God demands me for thy comforter; and comfort thee, stand by thee, and fight for thee, will thy leapingly-acknowledging brother, whom thy own father named Pierre!”[7]

Pierre’s entrance into this fate is begun through an act of self-narration, a beginning if you will. It is crucial that Pierre has produced this full structure of desire out of the slightest of notes delivered to him. He enters on the scene not only having decided on the truth of her statements, but in many ways what he is going to make of them. The entire arc of the narrative in both its ambiguously incestuous and its self-sacrificial motivations is already here. Perhaps the only thing that cannot be discussed is the relationship that this desire takes in regards to the history of Pierre’s family, or the structure of his family. We will need to look at that now.

Obviously when we look Casarino’s formulation of desire, there is something of the unconscious contained within this. To touch on this dimension, it seems crucial to deal with some of the ways that kinship works within the story. We can begin with the first relationship that is constructed fully within the novel, that between Pierre and his mother. We are informed that Mrs. Glendinning was widowed when Pierre was very young, and that the relationship with Pierre is very close. More specifically we are also informed that Pierre responded with what could be considered violent jealousy. Very well, it shouldn’t take an expert in psychoanalysis to recognize an Oedipal, incestuous element to this. But there is something else within this relationship that disturbs this comfortably pathological view of the family romance, the pair refer to each other as brother and sister. We are already in a position that puts us out of the range of an easy Freudian reading of the scene.

Beyond that ambiguity of the family structure, we are informed that the primary romantic attachment (other than his mother) is his cousin Lucy. What’s more he also had a youthful romance with his cousin Glen, which seems to have been dissolved because of their mutual desire for Lucy, and the fact that Pierre succeeded in winning her over. This transforms this relationship into one of mutual antagonism. We are in more of an economy that would be best described by Michel Foucault’s History of Sexuality Pt. 1. “The family, in its contemporary form, must not be understood as a social, economic, and political structure of alliance that excludes or at least restrains sexuality, that diminishes it as much as possible, preserving only its useful functions. On the contrary, its role is to anchor sexuality and provide it with a permanent support.”[8]

If I were going to put it in another way, I would say that the family relations that Pierre already is within act as the preconditions for the new structures of relations that he creates. In place of his mother turned sister, he takes on another illegitimate sister. He also reproduces the relations of the family that he ostensibly rebelling against by adding more and more female relations. The relations that are posited as legitimate and based in a mode of aristocracy are already illegitimate and illegible. The transgressive nature of Pierre’s act can only be tied unveiling the structure that already is in existence.

But we need to recognize that for Pierre, there is something new in creation, some genuine form of transgression. To understand that, we need to return to the question of individualism. In effect, this will allow us to bring the discussions of fate/desire and kinship towards their conclusion. This is because, although they are the prerequisites for Pierre to be produced, they also need to be repressed in order for Pierre to operate. We once again return to the figure of the time-namer, and the question can the time-namer for the age of ‘unfettered individualism’ recognize his position?

In reading the letter, Pierre is driven to make a number of reassessments of his the world that he lives in, from his father to his mother and his community (most prominently in the form of the priest.) He was clearly a product of the system that is linked with the seduction and abandonment of Isabel’s mother, slavery, and the extermination of American Indians. (Both of these are mentioned in the hallowed past of his ancestors.) The description that is offered captures this sense of despair. “The cheeks of his soul collapsed in him: he dashed himself in blind fury and swift madness against the wall, and fell dabbling in the vomit of his loathed identity.”[9]

No sooner does Pierre recognize the ambiguities of the lineage that he comes from then he tries to escape it. The portrait comes down only to leave a small impression of its existence. He is drawn to Isabel, his half sister out of the mystery that is contained in her parentage, and the fact that she is all but without parents in practicality. This is best exemplified by the tautological lyrics that draw Pierre in. “Mystery! Mystery/ Mystery of Isabel!/ Mystery! Mystery!/ Isabel and Mystery!”[10] We see this desire to destroy the past, to create the sense of individuality without parentage that is advocated in Melville’s small article on Hawthorne. On being disowned, he calls for the remnants of the past to be brought to them, and on their reception he destroys them.

A small wood-fire had been kindled on the hearth to purify the long closed room; it was now diminished to a small pointed heap of glowing embers. Detaching and dismembering the gilded but tarnished frame, Pierre laid the four pieces on the coals; as their dryness soon caught the sparks, he rolled the reversed canvas into a scroll, and tied it, and committed it to the now crackling, clamorous flames. Steadfastly Pierre watched the first crispings and blackenings of the painted scroll, but started as suddenly unwinding from the burnt string that had tied it, for one swift instant, seen through the flame and the smoke, the upwrithing portrait tormentedly stared at him in beseeching horror, and then, wrapped in one brad sheet of oily fire, disappeared forever.

Yielding to a sudden ungovernable impulse, Pierre darted his hand among the flames, to rescue the imploring face; but as swiftly drew back his scorched and bootless grasp. His hand was burnt and blackened, but he did not heed it.

He ran back to the chest, and seizing repeated packages of family letters, and all sorts of miscellaneous memorials in paper, he threw them one after the other upon the fire.

“Thus, and thus, and thus! On thy manes I fling fresh spoils; pour out all my memory in one libation!—so, so, so—lower, lower, lower; now all is done, and all is ashes! Henceforth, cast-out Pierre hath no paternity, and no past; and since the Future is one blank to all; therefore, twice-disinherited Pierre stands untrammeledly his ever-present self!—free to do his own self-will and present fancy to whatever end!”[11]

Pierre tries to reformulate himself, and recreate himself within this profound act of destruction. We obviously cannot ignore the Oedipal elements contained in this scene, Pierre is clearly engaged in an act of patricide, and the image of his father all but cries out at this act. But it doesn’t work within this economy as that Pierre burns his father to also reject his mother. He is more properly engaged in the revolutionary act of tabula rasa, but I think if we return to the removal of the painting, and the trace that remains, we can see the ultimate failure in this act. The trace points to the path already trod and repressed. It cannot be removed.

His acts of writing continue within this goal, but in the end they become failures as well. His editors refer to them as monstrosities and imposters. One is tempted to read the later output of his work as the production of so many symptoms. In trying to escape from his past, he winds up accomplishing only its repetition. We end in a sort of return of the repressed, with the ship sinking with the murder of Pierre’s cousin, and his suicide. That act ends the novel within the most trod upon tropes of the romance, one that can be found within Romeo and Juliet.

The novel then acts both within the desire for individualism, and, in a sense, an analysis of the symptoms produced. To return briefly to the figure of fate, it both produces the trajectory for Pierre’s narrative arc into the romantic individualism that he takes, and it undercuts its premises because, after all, it points to larger social forces that completely undercut the autonomy of the individual. The novel operates within the crisis of Jacksonian democracy, which seeks to create a radical democracy through the repression of what created it. One can find the diagnosis here, even as it itself is inured in the crisis.

[1] C.L.R. James, Mariners, Renegades, and Castaways: The Story of Herman Melville and the World We Live In (London: University Press of New England, 2001), 92.

[2] Herman Melville, Pierre, or The Ambiguities, Ed. Harrison Hayford, Herschal Parker, G. Thomas Tanselle (Easton, Illinois: Northwestern University Press, 1971), 211.

[3] Herman Melville Pierre, or The Ambiguities, Ed. Harrison Hayford, Herschal Parker, G. Thomas Tanselle (Easton, Illinois: Northwestern University Press, 1971), 62

[4] Herman Melville, Pierre, or The Ambiguities, Ed. Harrison Hayford, Herschal Parker, G. Thomas Tanselle (Easton, Illinois: Northwestern University Press, 1971), 45.

[5] ibid., 182

[6] Cesare Casarino, Modernity at Sea: Melville, Marx, Conrad In Crisis (Minneapolis, Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 2002).

[7] Herman Melville Pierre, or The Ambiguities, Ed. Harrison Hayford, Herschal Parker, G. Thomas Tanselle (Easton, Illinois: Northwestern University Press, 1971), 66.

[8] Michel Foucault, The History of Sexuality: Volumen I: An Introduction, Trans. Robert Hurley (New York: Vintage Books, 1978), 108.

[9] Herman Melville Pierre, or The Ambiguities, Ed. Harrison Hayford, Herschal Parker, G. Thomas Tanselle (Easton, Illinois: Northwestern University Press, 1971), 171.

[10] Herman Melville Pierre, or The Ambiguities, Ed. Harrison Hayford, Herschal Parker, G. Thomas Tanselle (Easton, Illinois: Northwestern University Press, 1971), 126.

[11] Herman Melville Pierre, or The Ambiguities, Ed. Harrison Hayford, Herschal Parker, G. Thomas Tanselle (Easton, Illinois: Northwestern University Press, 1971), 199

However I plan on touching on three separate topics within the book. The first deals with the way that the family history of Herman Melville circulates within the text. This will then move into a discussion of the notion of ‘fate that is circulated through the book. I look at the connections that this has with Melville’s earlier novel Moby Dick, and look at how this connects to desire. From there I want to move into a discussion of the structures of kinship that work within the book, which are always within a state of transgression. All of these coalesce in the desire for individualism, a desire that is intimately linked to the repression of that which allowed for the subject’s production.

It’s difficult to discuss the book Pierre without noting some of the prominent similarities between the heritage of Pierre and Melville’s own life. I turn briefly to CLR James’ reading for some of these details.

Both his grandfathers were heroes of the Revolutionary War. His father was a merchant, an importer of foreign merchandise. Melville was thus by birth a member of that landed and commercial aristocracy which, even after 1776, held the first place in American society until Andrew Jackson gave it a mortal wound in 1828. The Melville family felt this personally. Herman’s grandfather, Major Thomas Melville, was removed as Naval officer for the Port of Boston by the new Jackson administration. Other calamities were in store. In 1832 a depression ruined his father and the blow caused his death. The Melvilles were ruined. Herman was then thirteen years old. Around him, henceforward, the old America was passing, and a new America was taking its place in a turmoil that grew increasingly.

Machine production was breaking up the old artisan industry. Between 1840 and 1850, far from the frontier offering an outlet for the bold and energetic in the East, there was a movement back from the farms to the cities. The old sense that men had of being members of an integrated community, which the winning of Independence had not destroyed, was now in process of dissolution. This is a society in which young Melville grew up. Unchecked individualism was coming to maturity and Emerson, a favorite author of Henry Ford, understood the change and celebrated it.[1]

We find ourselves confronted with an image that is extraordinarily similar to the familial background of our main character, Pierre. I am, of course, aware of the injunction that we are not to read the biography of the author into the text, but Melville is a rather interesting case in this instance. Despite the failure of Moby Dick, Melville could be argued to be one of the first examples of what could be called a celebrity writer, and what’s more one that succeeds within this project through a certain project of self-mythologisation. The text of this history is not only written into the text of his novels, but also into a countless series of newspaper and magazine articles. I would argue that the figure of the history of Melville is a much of an act of intertextuality as the incorporation of the texts of Dante or Shakespeare.

Similarly Melville sites himself within his text. This can be found in the descriptions in the family life of Pierre, the reception of the critics to his works, and a number of other places. I would like to connect this with the torn pamphlet that Pierre reads in the middle of the novel, “Lecture First. Chronometricals and Horologicals.” “For peculiarly coming from God, the sole source of that heavenly truth, and the great Greenwich hill and tower from which the heavenly truth, and far out into infinity reckoned; such souls seem as London sea-chronometers (Greek, time-namers) which as the London ship floats past Greenwich down the Thames, are accurately adjusted by Greenwich time, will still give that same time, even though carried to the Azores.”[2] The piece goes on with the analogy, arguing that the chronometer would act out of sync with the times of China. One could say that one is only a time-namer for a particular place, and perhaps even time.

I want to read Pierre within this notion that Melville introduces us to, that of the ‘chronometer, the time-namer.’ We have already touched on the notion of transition earlier in our discussion. James the good marxist that he is has already noted for us that there was a radical shift in the nature of the republic that was occurring at that time, this is marked by all the usual signs of industrial capitalism, the collapse of artisan production, communities, urbanization, etc. But more significantly for this narrative, he marked the production of a sort of unfettered individualism within this. Pierre, and indeed the rise of the figure of Melville, fits well into this narrative. There is an interesting reading of this within Wai-chee Dimock’s Empire for Liberty: Melville and the Poetics of Individualism that reads Melville symptomatically of these times. I am sympathetic to this reading, and never want to suggest that the text escapes this, but it seems that alongside this desire for unfettered individualism is a critical examination of it. After all, the text marks this passage, and notes that Pierre cannot understand it, even upon multiple readings. One cannot act as a time-namer of the collective desire for unfettered individualism and simultaneously recognize that fact.

The figure of Melville operates within this poetics of individualism. He had operated within it for some time before the publication of Pierre. His earliest work was published as a memoir, and his most popular works were published under the authority of a man that has been to sea. He was the man who read into Hawthorne’s Mosses the production of a genuinely American form of art, one that orphaned itself from its European roots. At the same time, the desire to fulfill this narrative placed Melville in opposition to the audience that held that same myth in common. We can see a profound contradiction between the “I” of Melville that desires to be the “great artist” as opposed to the “I” that was desired by the publishers and the audience of the day, an “I” that is associated with a sort of authentic self, and its journeys.

We will need to return to this discussion of the circulation of the politics of the individual that circulates in such a vexed and complicated manner within the text, but we first need to deal with the method in which the plot moves forward, namely the question of fate. This term, which appears frequently within the text, is not unique to it. It also acts as an important feature of the narrative structure of Moby Dick. Ultimately, we will see that it both explains and undercuts the individualism discussed above.

What does it mean to enter into the formation of time, of the times I suppose that Pierre is naming? I want to enter into this discussion with the figure of Fate. Fate is one of the most interesting parallels between the text of Pierre and that of Moby Dick, both are driven by a mysterious force that is given the name ‘Fate.’ For Ishmael, fate is linked to the fatal voyage that he embarks upon. For Pierre (who is also marked as Ishmael within the text) fate enters with the entrance of the letter that will pull him from his old way of life. “He equivocated with himself no more; the gloom of the air had now burst into his heart, and extinguished its light; then, first in all his life, Pierre felt the irresistible admonitions and intuitions of Fate.”[3]

This figure of Fate acts to drive him to secretly visit his illegitimate sister, abandon his finance and mother, marry his half sister and leave his home and city. We can see the intensity that comes from his initial connection with Isabel. “Never had human voice so affected Pierre before. Though he saw not the person whom it came, and though the voice was wholly strange to him, yet the sudden shriek seemed to split its way clean through his heart, and leave a yawning gap there.”[4] Indeed Fate is presented as a powerful force, one that pushes through and beyond the individual. “So, though long previous generations, whether of births of thoughts, Fate strikes the present man. Idly he disowns the blow’s effect, because he felt no blow, and indeed, received no blow. But Pierre was not arguing Fixed Fate and Free Will, now; Fixed Fate and Free Will were arguing him, and Fixed Fate got the better of the debate.”[5]

Indeed, I agree with Cesare Casarino’s reading of Fate within Melville’s economy. “Fate is desire. To catch a glimpse of the future one feels fated to fulfill is here understood as the form taken by the desire for that future, as a claim-staking over its as yet “unapproachable and unknown” territories: to foresee and to want are produced here as the Janus-headed process propelling the discourse of fate…. For Ishmael, fate is produced both as the materialization and as the displacement of a desire too great and unconfessable to be made manifest any form other than a policing exteriority, a ponomphean deus ex machina hovering and looming high above the stage on which the drama of whaling is about to unfold.”[6]

The desire that Casarino is invoking doesn’t operate within the romantic economy even though it can be mystified into such a position. Instead this formation of desire is a productive force that cannot be conceived of either as an outside or a completely immanent force. It cannot be conceive within the economy of the outside because it is so linked to the becoming of the subject in question, but neither can it be conceived as immanent because it draws on the forces that produced the subject. As a force it is productive and overdetermined. It pushes the subject into a futurity that he does not even complete understand himself.

Just as Fate acts within the economy of Moby Dick, there is a comparable role played within Pierre. We can find the explosive nature of this very early within the structure of the novel.

Pierre now seemed distinctly to feel two antagonistic agencies within him; one of which was just struggling into his consciousness, and each of which was striving for the mastery; and between whose respective final ascendencies, he thought he could perceive, though but shadowly, that he himself was to be the only umpire. One bade him finish the selfish destruction of the note; for in some dark way the reading of it would irretrievably entangle his fate. The other bade him dismiss all misgivings; not because there was no possible ground for them, but because to dismiss them was the manlier part, never mind what might betide. This the good angel seemed mildly to say—Read, Pierre, though by reading thou may’st entangle thyself, yet may’st thou thereby disentangle others. Read, and feel that best blessedness which, with the sense of all duties discharged, holds happiness indifferent. The bad angel insinuatingly breathed—Read it not, dearest Pierre; but destroy it, and be happy. Then, at the blast of his noble heart, the bad angel shrunk up into nothingness; and the good one defined itself clearer and more clear, and came nigher and more nigh to him, smiling sadly but benignantly; while fort from the infinite distances wonderful harmonies stole into his heart; so that every vein in him pulsed to some heavenly well. (Melville 63)

In receiving the letter, Pierre has the intuition that this will some how radically change his life, and he is given the choice whether to stay in the place where he is, or move elsewhere. Within that, he decides upon opening the letter. It is curious that while the decision is a displaced one with the figures of angels acting as litigants, the joy that is gained from the decision is Pierre’s even if he cannot fully understand it. And what is contained in the letter but the thing that he has most wanted in the world, a sister. When one looks at the response that Pierre has to the letter, it is clear that his acceptance of its truth is a form of desire for that very truth. One can see this in his final acceptance of the letter.

“This letter is not a forgery. Oh! Isabel, thou art my sister; and I will love thee, and protect thee, ay, and own thee through all. Ah! Forgive me, ye heavens, for my ignorant ravings, and accept this my vow.—Here I swear myself Isabel’s. Oh! Thou poor castaway girl, that in loneliness and anguish must have long breathed the same air, which heaven hath placed in my hands; sweet Isabel! Would I not be baser than brass, and harder, and colder than ice, if I could be insensible to such claims as thine? Thou movest before me, in rainbows spun of thy tears! I see thee long weeping, and God demands me for thy comforter; and comfort thee, stand by thee, and fight for thee, will thy leapingly-acknowledging brother, whom thy own father named Pierre!”[7]